Question Your World: Are There 36 Intelligent Civilizations in the Galaxy?

As life on Earth continues to carry on we still find occasional moments in the night to look up at the blanket of stars above us and wonder if any life is out there looking back at us wondering the same thing. The possibility for intelligent life has certainly captured human imagination and curiosity for centuries. Through our history we've come up with myths, legends, lore and stories about what kinds of life could exist out there, but how would we actually find out how many civilizations are out there? Some researchers have been working on that exact question and now have an equation that says there could be 36 civilizations for us to communicate with in our galaxy. This brings to mind an immediate and huge question: Are there 36 intelligent civilizations in the galaxy? And how did they come to that conclusion?

In 1961 The Drake equation gave humanity a scientific way to estimate how many intelligent civilizations we might be able to communicate with across our galaxy. It requires us to know things like how many stars are forming in the galaxy, how many stars form planets and how often life develops. Now some scientists are taking a different approach.

One important variable when pondering intelligent communicating civilizations is the time needed for those civilizations to evolve. Our one and only example is the Earth, where it took about 4.5 billion years for intelligent life to become broadcast communication friendly. This new equation starts by assuming that intelligent, radio-broadcasting civilizations need about 5 billion years to get started.

Image credit: Getty Images

Their new approach is being called the Astrobiological Copernican Principle, a nod to the original Copernican Principle. The Copernican Principle originated in mid-20th century cosmology and stated that Earth was not at a privileged place in the universe. So whatever we see here should apply everywhere. Originally intended to apply to the large scale structure of the universe, these authors have said that the timeline for intelligent life to develop should be similar across the galaxy. Basically, because life took about 4.5 billion years to develop radio communication capabilities, life must always need about that much time, no matter where that life is located.

From there, the history and evolution of stars in our galaxy leads to new limits on how many neighbors we might have. Not all of the variables involved are extremely well-known, so the authors end up with a range of results based on how strict their initial estimates were.

For the optimists, there could be billions of inhabited planets in the Milky Way, and perhaps a thousand civilizations able to communicate across the galaxy. For a pessimistic astronomer, the galaxy is more than half empty — they might settle on a much smaller number of communicating civilizations: 36.

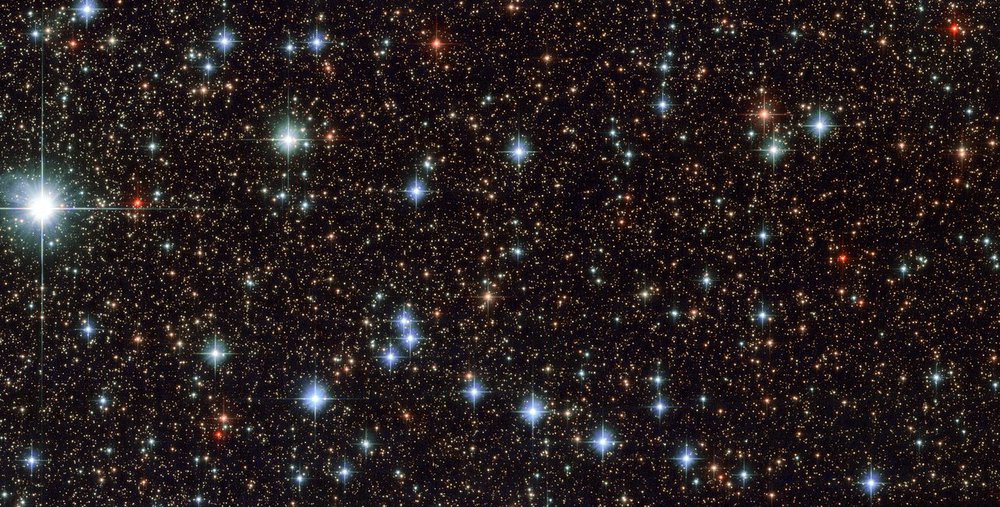

Image credit: NASA

Now enter the next big challenge: space. There’s a lot of space in space so communication between said potential civilizations would be something to consider as well. We have been able to emit signals into space for a hundred years, so our signals have only reached 100 light years from our home.

According to these researchers the distance to our nearest neighbor could be as much as 17,000 light years, making back and forth communication in an individual human lifetime impossible. Even if extraterrestrial broadcasts are already criss-crossing the galaxy, we might need to search for over 1,000 years before the next one reaches us.

Our communications to one another and the species on this planet is a much more immediate relationship for us to actively be involved with, but some scientists continue to look outward in hopes of helping us better understand our place in the cosmos, regardless of how long it took for life to develop here. In the words of America's foremost expert on all things extraterrestrial, the truth is out there.

The Museum is hard at work helping you to discover your world despite dramatically reduced financial resources. If you'd like to help us continue this work, click here to learn how.