The Hunt for Exoplanets: One of the Most Exciting Topics in Modern Astronomy

Hi, everyone. It’s Justin Bartel, the Science Museum of Virginia’s resident astronomer. If you’ve visited The Dome for one of our planetarium shows, there’s a good chance you’ve heard a little about one of the most exciting topics in modern astronomy: exoplanets.

We’ve long known that the sun was an unspectacular star, just one of billions in the Milky Way galaxy, so why should the sun’s system of planets be unique? It took awhile for technology to catch up with astronomers’ speculations, but in the mid-1990s we were finally able to detect evidence of planets orbiting other stars.

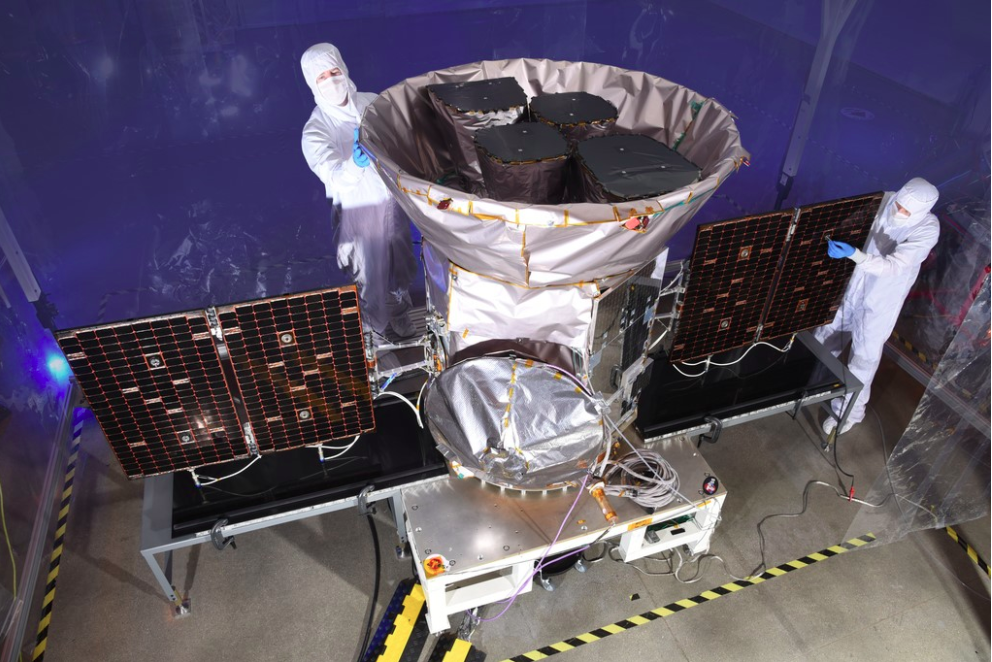

TESS undergoing final preparations for launch. Notice the relatively small size of the spacecraft. Credit: Orbital ATK

Today, the number of confirmed exoplanet discoveries is approaching 4,000! More than half of these were discovered by Kepler, a space telescope launched in 2009, but after almost a decade of operation its fuel tanks are running low and its mission will soon end. Just in time, a new exoplanet hunter named TESS has been sent into orbit.

Thanks to the NASA Social program (an initiative that allows NASA's social media followers to go behind-the-scenes at facilities and events, and speak with scientists, engineers and astronauts), I had the honor to go to Florida to see the TESS launch in person. Let’s take a closer look at the mission, its ride into space and what we all have to look forward to when science data starts streaming down to Earth.

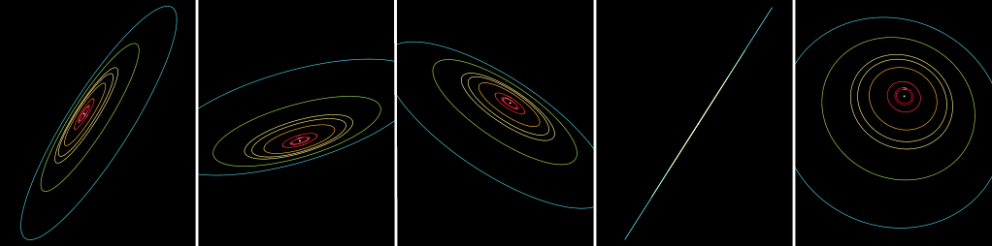

Here is a planetary system viewed from five different angles- only one of these is likely to produce transits. For Earth-sized planets orbiting Sun-like stars, we only expect transits to be possible in about 1 percent of planetary systems.

The first thing we should cover is the mission’s name, TESS. It’s an acronym for “Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite” and although that’s certainly a mouthful, it’s not too difficult to unpack its meaning (unlike some missions I’ve seen leave Earth. I’m looking at you OSIRIS-REx!).

We’ve already covered “exoplanet” – a planet orbiting another star – and “satellite” hardly needs an explanation as we enter the seventh decade of the space age. “Survey” describes the mission’s goal to observe stars across a large portion of the sky rather than just focusing on a small region or a few targets. Over the next two years, TESS will monitor more than two million stars spread across 85 percent of the sky! Why look at so many stars? It’s to increase the odds of finding “transiting” exoplanets.

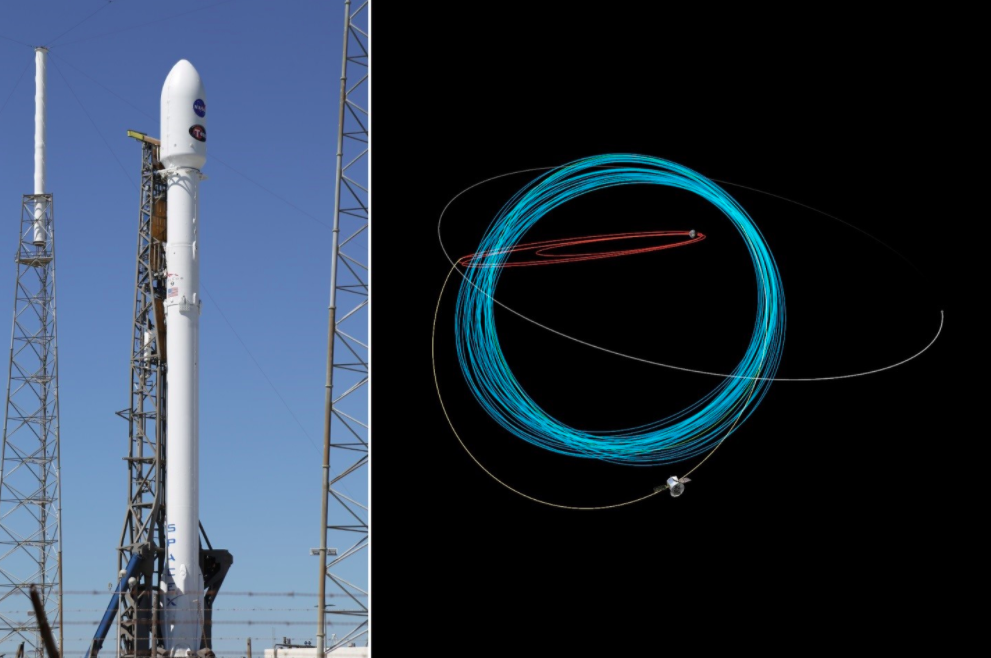

(left) The TESS Falcon 9 rocket on the launch pad prior to the scheduled launch on April 16, 2018. (right) The position of TESS on May 25, 2018, is marked on this view of its trajectory. Its first few orbits are shown in red – these orbits were used to line up for a lunar flyby on May 17 that pushed the spacecraft toward its unique science orbits, colored blue here. You can always visit the Museum’s Dome to see where TESS is now.

As the solar eclipse last August reminded us, it’s not every day that celestial bodies line up perfectly so that one passes in front of another. The orbits of exoplanets can be arranged at any angle around their star, so viewed from the Earth, most will pass above or below their host star undetected by spacecraft like TESS. But there will be some exoplanets with orbits aligned so they appear to move across the face of, or transit, their host star when viewed from Earth. If we monitor the brightness of the star carefully, we can see it get just a little dimmer when the planet is in the way.

TESS is a small spacecraft with a big mission, and to help it get off on the right foot, NASA selected the SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket to carry it into space. One of the highlights of the NASA Social experience was a trip to the launch pad to see the rocket up close. There were nearly 1,000 feet separating us from the base of the rocket, but it was still an impressive sight!

As I stood at the Kennedy Space Center on April 16 – 754 miles from my normal star-gazing post in the Museum’s Dome – I realized that if everything went as planned, it would just be a few hours before the pad was evacuated and TESS was sent into a high Earth orbit on a pillar of rocket exhaust.

The launch of TESS on a Falcon 9 rocket on April 18, 2018.

Things did not go as planned. While we continued our tours of Kennedy Space Center, SpaceX engineers continued their checkout of the rocket’s systems to ensure everything was ready for launch. The team found a potential problem with the SpaceX guidance, navigation and control system, and rather than risk leaving TESS in the wrong orbit, they made the decision to delay the launch by 48 hours to analyze the issue.

FYI: this is the sort of thing you should always consider if you want to travel for a rocket launch – problems with the rocket, bad weather and even unauthorized boats and aircraft in the launch zone can cause delays! On a positive note, I got to stay in Florida a few extra days, which wasn’t a bad way to spend my birthday.

After two days of waiting, the NASA Social group gathered again on April 18 and this time everything was picture-perfect. The weather was clear, the guidance problem had been reviewed and the Falcon 9 carried TESS into space.

You can watch launches online and be treated to spectacular camera views, but there’s something special about seeing it in person, even if the rocket looks a bit smaller from over three miles away. I can’t think of a more dramatic demonstration of the difference between the speed of light and speed of sound. The first thing you see is the flash of the rocket engines igniting, and then the rocket silently rises off the pad. After a few seconds, the sound arrives and rattles the air in a way you’ll never hear on TV. And then, as the Falcon 9 approaches 1st stage separation just over two minutes into the flight, the rocket has already flown so high and so far that it fades from view.

TESS recently captured this test image using one of its four cameras. It shows about 200,000 stars along the plane of the Milky Way in the constellation Centaurus. The mission’s full survey will cover an area more than 400 times larger than this single image.

One sight currently unique to SpaceX launches that I was hoping to see is the return and landing of the 1st stage booster. But TESS was being sent on a trajectory that would send it out as far as the Moon’s orbit in the following days, so the rocket wasn’t able to preserve fuel for a return to the Florida coast. Not long after I lost sight of the rocket, the 1st stage did return to Earth, landing on an autonomous drone ship in the Atlantic Ocean. It will be prepared to fly again on a future mission.

The fairings used to protect TESS at it traveled through the atmosphere were dropped in the ocean, too, and SpaceX is still learning how to recover them for reuse. The 2nd stage of this rocket was sent even farther than TESS itself, leaving Earth’s gravitational control and entering orbit around the Sun. On future low-Earth orbit launches, the 2nd stage of the Falcon 9 rocket may be recovered and refurbished as well.

TESS is in the midst of about two months’ worth of instrument calibration and orbital maneuvers prior to the start of its science campaign in mid-June. Its cameras have been powered on and the spacecraft is using its instruments to determine its orientation in space and point in the right direction. You can follow the latest updates from the mission on Facebook and Twitter.

Dr. Doug Hudgins (left) with Science Museum of Virginia’s astronomer Justin Bartel in Florida for the launch of TESS on April 18, 2018

Once the search for planets begins, data will be sent back to Earth every two weeks and analyzed for transit signals. The science team has selected 200,000 stars that will have their brightness measured every two minutes, and about two million will be tracked every 30 minutes. These targets are spread over the entire sky, so TESS won’t be watching all of them all of the time, but it will still produce a huge amount of data. After initial processing, the TESS team will make the data available for anyone to access so it’s hard to say when someone will find the first planets. There’s the possibility that it could be before the end of this year. By the conclusion of mission, TESS is expected to find more than 10,000 exoplanets – 2-3 times more than we’ve found using all of the telescopes and techniques at our disposal over the last quarter century!

The launch of any spacecraft is a brief moment amidst years of planning, assembly and testing followed by observation, analysis and discovery. But because of the excitement of that moment, the launch tends to attract scientists, engineer, and administrators connected to the mission, so you never know who you might meet.

Although the NASA Social officially ended immediately following the launch, my experience was enhanced by meeting the Program Scientist for NASA’s Exoplanet Exploration Program, Dr. Doug Hudgins. He was kind enough to answer questions and share insight on the TESS mission and exoplanet science in general that helped put the day’s launch in context with our search for new worlds beyond our solar system.

The rocket put on quite a show at launch and I’m fascinated by the capabilities of the spacecraft, but this chance conversation with Dr. Hudgins was a nice reminder that hardware never gets a chance to shine without curious and dedicated people. The TESS mission and the search for exoplanets isn’t simply about cataloging the contents of the universe – we’re trying to understand how unique our solar system might be, how Earth compares to other planets and whether our home is the only world capable of supporting life like us.