Retirement Reflections: Top 5 Most Interesting Kepler Finds

Hi, everyone. It’s Justin Bartel, the Science Museum of Virginia’s resident astronomer. On Tuesday, October 30, NASA announced that the Kepler space telescope had run out of fuel and would be retired. The mission’s story dates back 35 years, even before we knew for sure that planets existed around other stars (now called exoplanets).

In 1983, NASA scientist William Borucki wondered if we could find small, Earth-sized worlds if they passed in front of (or transited) their host star, blocking a bit of the starlight from reaching the detectors of our telescopes. After nearly two decades of work, four rejections by NASA review boards and multiple name changes, NASA accepted the Kepler concept in 2001 and work began to build and launch the telescope.

Kepler, named for the 17th century astronomer who devised the laws of planetary motion, launched into space in 2009 and quickly transformed what we know about exoplanets. Roughly 300 exoplanet discoveries had been publicly announced prior to Kepler’s launch; Kepler discovered 2,662 over the next nine years.

With so much time and so many discoveries, it’s impossible to write a complete list of Kepler highlights that you can read in one sitting, so here is an incomplete countdown of interesting things Kepler found:

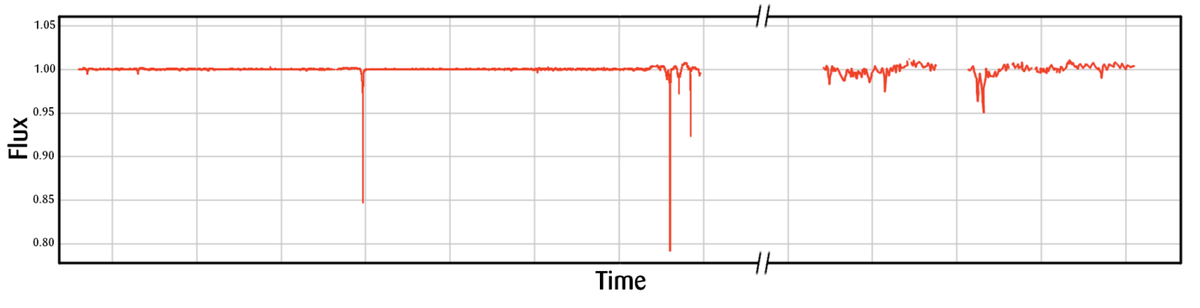

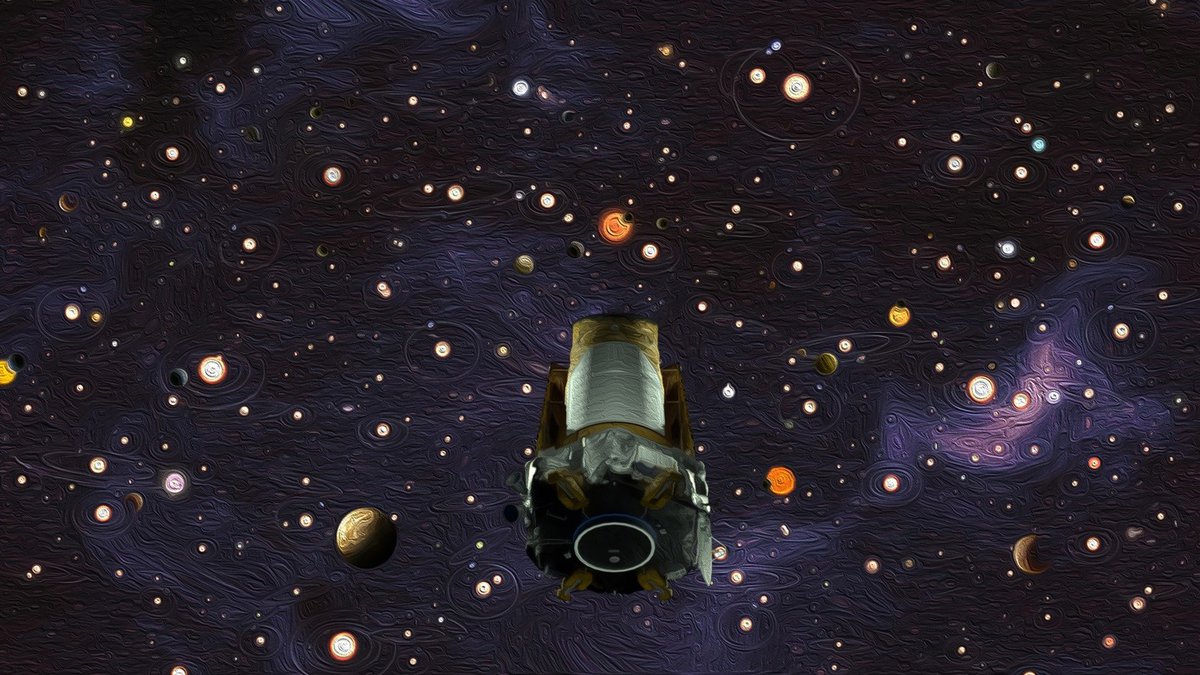

Image credit: Justin Bartel, Science Museum of Virginia

Tabby’s Star, a citizen-science mystery

In early 2016, citizen scientists participating in the Planet Hunters project found a strange star in Kepler’s data archive. Volunteers participating in the project spent some of their spare time looking for new planets that computers hadn’t picked out of the data yet. A transiting planet would create small, regularly spaced dips in the star’s brightness, but the target labeled KIC 8462852 showed wild and irregular dips in brightness – sometimes dimming by as much as 20 percent. This is not at all what Kepler scientists expected to see!

After the science team received word of this star from Planet Hunters users, science team member Dr. Tabetha Boyajian led the investigation into what was going on with the star (which would go on to be nicknamed after her). When another astronomer suggested the dimming Kepler observed could be caused by a gigantic structure built by an alien civilization, the press reacted instantly and a flood of headlines about Tabby’s Star and aliens drowned out the ongoing investigation. A successful crowdfunding campaign allowed Boyajian’s team to pay for continuous observation from commercial telescopes and subsequent analysis suggested the culprit was rather mundane: space dust.

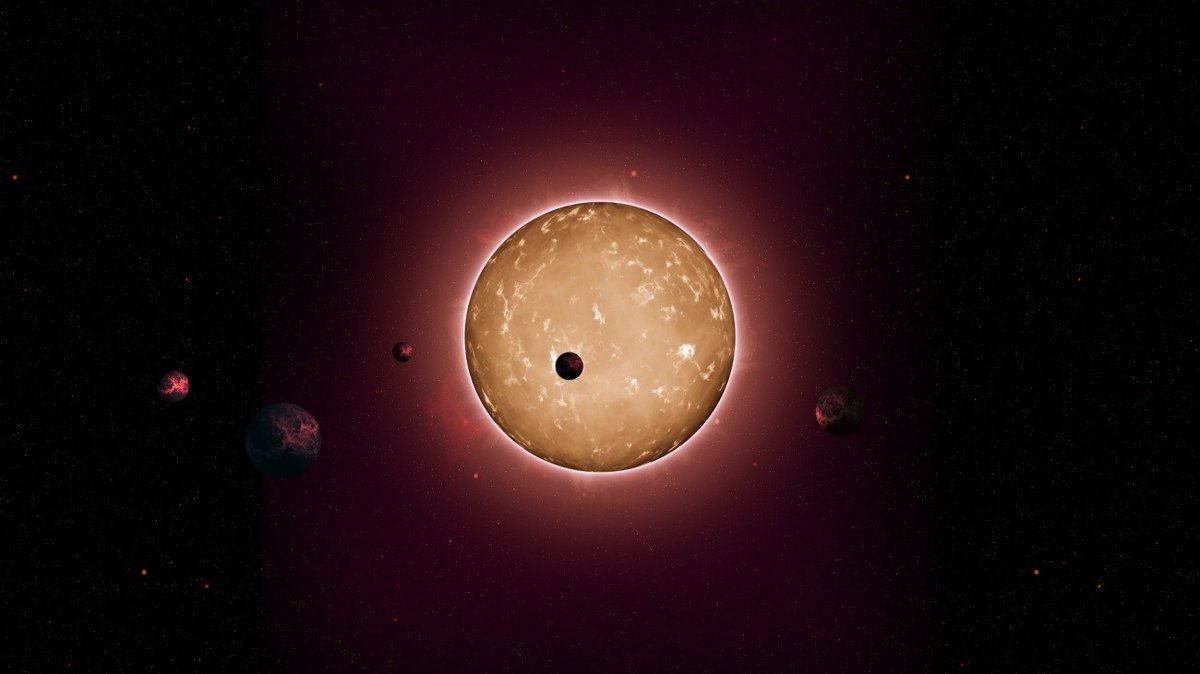

Image Credit: Tiago Campante/Peter Devine

Kepler-444, ancient worlds

In January 2015, the discovery of five planets orbiting a star 119 lightyears away was announced. These planets are not only among the smallest Kepler discovered (all five are bigger than Mercury but smaller than Venus), they are also the oldest. Kepler-444 is a dwarf star slightly smaller and cooler than the Sun, with an estimated age of 11.2 billion years – more than twice as old as our Sun. This star has been shining for more than 80 percent of the time since the Big Bang!

At the time of Kepler-444’s formation, the ingredients for terrestrial planets should have been less common than they are today, and yet this little star gathered enough for at least five rocky worlds. The planets of Kepler-444 are all very close to their star, and if they’ve been broiling for 11 billion years the odds of life developing there were incredibly thin. That said, their existence opens the door to other rocky planets forming in that early epoch and it’s easier to imagine life developing elsewhere, perhaps billions of years before the Earth was even a mote of dust.

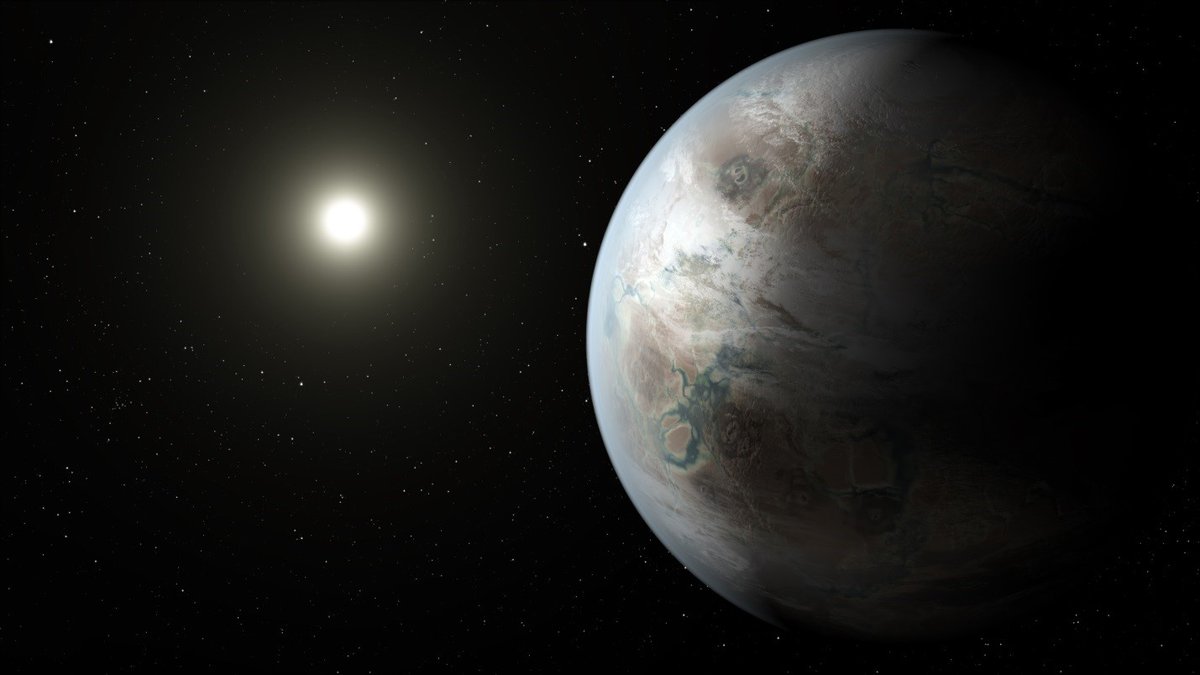

Image Credit: NASA Ames/JPL-Caltech/T. Pyle

Kepler-452b, Earth’s big cousin?

One of the major goals of the Kepler mission was to identify small rocky planets that might be as friendly to life as Earth is, and in 2015 Kepler revealed its best candidate for another habitable world. A true Earth-like planet would orbit a middling star at just the right distance to allow liquid water to flow across its surface to nourish the lifeforms calling it home.

Kepler-452 is a star very much like the Sun, but just a bit older, larger and brighter. Kepler-452b orbits at nearly the same 93-million-mile distance we find ourselves from our Sun, so its surface temperatures could be similar to Earth’s if it has an atmosphere like ours. And it’s here we find an important limit to Kepler’s abilities. This mission was designed to measure the orbits and sizes of exoplanets, but it can’t determine a planet’s composition, atmospheric makeup or other details that make a planet habitable. In fact, the case of Kepler-452b gets a bit stranger if we take its size into account: it measures about 1.5 times the Earth’s diameter, and carries about 5 times Earth’s mass.

Computer models and the examples in our solar system show that at some point planets larger than Earth transition to being more gaseous than rocky – the universe doesn’t seem interested in making a rocky planet the size of Jupiter, or even one as large as Neptune. Some estimates put the upper limit for rocky planets very close to Kepler-452b’s size, so “Earth 2.0” may be closer to Neptune 0.5.

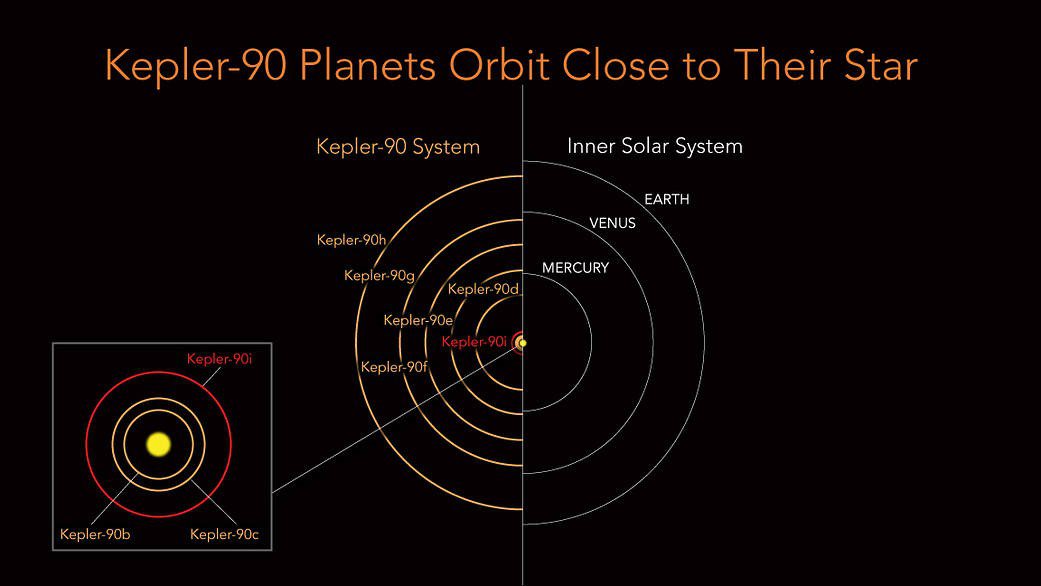

Image Credit: NASA/Ames Research Center/Wendy Stenzel

Kepler-90, reminding us of home:

About 60% of known exoplanets are, as far as we know, orbiting their star alone. Multi-planet systems like the one we live in are rare finds, and until December 2017, we hadn’t identified another planetary system with more than seven planets. Then NASA partnered with Google to analyze Kepler data using an artificial intelligence technique called machine learning to teach computers how to recognize new planets.

When the newly trained computers went through old Kepler data, it found a planet orbiting Kepler-90 that had escaped detection in 2014, increasing that system’s known population to eight and matching the number of planets in our solar system! The smallest planet orbiting Kepler-90 is just a little larger than Earth and the largest is roughly the size of Jupiter, and just like we see at home, the small planets orbit closer to their star while the gas giants are farther away.

Despite the similarities, the wrinkle at Kepler-90 is how close the planets are to each other – all eight of them orbit close to their star, in a region where our solar system has just three planets (Mercury, Venus and Earth). Because Kepler-90 is similar in size and temperature to the Sun, the inner rocky planets are very hot and it’s hard to imagine they’d be friendly to life. But, if any large rocky moons orbit the outermost Kepler-90 gas giant, they would be in the system’s habitable zone.

Image Credit: NASA/Ames/W. Stenzel

More planets than stars:

Each individual discovery was amazing in its own way, but the most important thing Kepler showed us is the big picture. Kepler found a huge number of planets, but the transit method it used is fairly inefficient – most exoplanets will not transit their host star. Those facts together – observing a lot of instances of a rare event – suggest that planets are everywhere!

Based on Kepler’s rate of discovery, astronomers were able to estimate that on average each star in the Milky Way has 1.6 planets. Like the Pew Research Center’s estimate of 2.4 children per mother, that partial planet is introduced by the math, not unusual planetary physics. And looking at our own solar system, this shouldn’t be too surprising: planets outnumber stars here by at least 8 to 1. Add the Kepler-90 system to the mix and we have two stars that have managed 16 planets. Such large systems still appear exceptional (though that’s due in part to the limited time Kepler was able to observe its target stars) but a few of them can cover for stars that may not have formed planets of their own.

In the end, it’s fairly safe to look up to the sky at night, pick a random point of light and assume that at least one planet is circling that faraway star. Kepler has revealed a galaxy overflowing with new worlds and new possibilities for scientists, artist, and dreamers alike. Kepler’s discoveries have been stranger and more varied than we could have predicted or imagined.