What's the Dirt on Soil?

Right now The Green–the Science Museum’s future six-acre community greenspace–is more brown than green and hardly the urban oasis we’re working toward. In fact, it’s acres of barren earth patiently waiting for horticulture experts to plant thousands of flowers, shrubs and trees later this year. (Yes, the entire project includes more than 6,000 plants!)

But what may look like unassuming or unflattering dirt to bikers, drivers and bus riders traveling along Broad Street, enthusiasts see as soil filled with a magnitude of stories that will all impact the health of our plants in some way.

A panoramic photo of The Green taken from the top level of the Science Museum's parking deck on February 14, 2022.

While people sometimes use the words interchangeably, there’s a difference between dirt and soil. Soil is the official scientific term that refers to the loose, unconsolidated mineral and organic matter filled with microorganisms in the upper layer of the earth's crust. Dirt is the colloquial term for soil that gets displaced and makes you unclean. Once soil gets stuck to your shoes or under your fingernails from working in the garden, it loses properties that allow it to sustain life and becomes dirt.

Soil is an ecosystem unto itself, and its quality can have a huge impact on the vegetation growing within it. Plants use soil to anchor themselves to the earth, insulate their roots and receive water, air and nutrients. While full of nutrients and microbes healthy plants need, only about 10% of the earth’s surface contains soil.

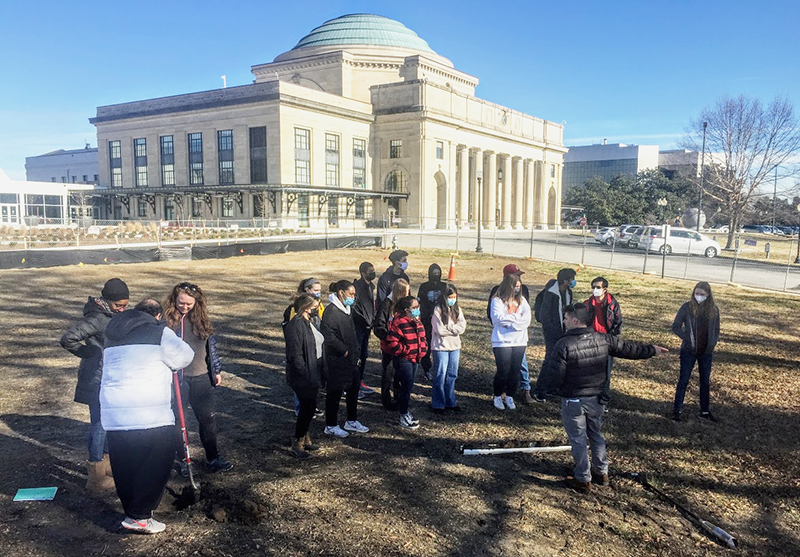

VCU SustainLab students taking soil samples on The Green in early February 2022.

As we prepare to populate The Green with a wide variety of native plants and trees, first we have to figure out what we’re working with when it comes to the soil. We’re concerned about both non-living and living soil conditions, and have to identify any areas that need improvement. That process involves inspecting various non-living soil properties: texture, structure, chemical elements and pH.

To understand the living properties, experts have to look at soil from The Green under a microscope to determine which microorganisms are present.

Good soil is full of life, containing organisms such as mycorrhizal fungi, bacteria, nematodes, protozoa, arthropods and earthworms. Most of these organisms live in the top four inches of the surface soil and form the soil food web. Many of these creatures are so small that researchers must use microscopes to study the plethora of life living in this layer of soil. These microorganisms form a beneficial relationship to the plant's root system and assist in delivery of nutrients. Without the soil food web, plants struggle to thrive.

In urban environments there is a lot of human activity that negatively impacts the soil and makes it less habitable for life. Toxic chemicals such as oil, gasoline and pesticides enter the soil, which can ward off life forms. In addition, soil compaction (remember, the area where The Green is going was a parking lot filled with nearly 100 heavy vehicles for years and years) doesn’t allow sufficient exchange of air and water to support life.

VCU professor Dr. Stephen Fong talks to students about The Green's soil.

Luckily for us, we have a local partner to help us learn more about our soil! Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) students taking the SustainLab course, which focuses on urban ecology and sustainability, recently visited The Green. They dug soil pits to compare soil structure and texture of undisturbed urban soil and to that of soil from the construction site. Under guidance from course instructors Dr. Stephen Fong and Dr. Chris Gough, the students will incorporate our samples into their research on topics related to soil, plants, water and atmosphere.

We already knew depaving the asphalt parking lot left very little of The Green’s top soil layer. We brought in soil containing organic matter and spread it over the entire site to help restore a healthy soil layer. Adding organic matter to the soil creates a more hospitable environment for microorganisms. In addition, during The Green planting process, we’re mixing mycorrhizal inoculant (those beneficial fungi) into the upper six-to-eight inches of the soil next to each plant’s roots to promote important nutrient processing.

In addition to that work, we’ll use the VCU student’s analysis to help inform the installation and maintenance plan for The Green, making alterations to the plant selection, placement and soil amendments as needed. The information they provide will also allow us to better understand how to take care of our plants once they are in The Green.

This work may be dirty, and takes a little time, but it’s important prep before a single purple coneflower or Eastern redbud ever makes it to our campus. Don’t worry … the lush community park is coming. Just like when building a house, we have to get the foundation in perfect condition first so we can build a thriving and beneficial home for plants, insects and wildlife!