Question Your World: Why Is This Black Hole Picture So Important?

Every now and then, there is a science event that makes the entire planet pause for a second and appreciate the results of knowledge, cooperation, and innovative thinking. That sort of thing just happened as the world got a look at the first ever image of a Black Hole! Why is this black hole picture so important?

The planet celebrated a huge scientific accomplishment this week. Humanity was able to share its first photo of a black hole! This is a pretty huge project that spanned years, involved thousands of bright thinkers, and over 800 computers! The Event Horizons Telescope, a global network of radio telescopes, was used by astronomers to peer out into the vastness of the cosmos and focus on a super massive black hole in the distant M87 galaxy. Black holes are so dense and have such a strong gravitational field that anything that falls in can never escape, even light!

Observations for this project stopped in 2017, but it took a while to get all the data from the various telescopes sorted out. The South Pole Observatory in Antarctica was closed from April through October of 2017 due to the dangerous and extreme cold of the Antarctic winter. In December of 2017 when conditions were a bit more manageable, scientists were able to acquire the South Pole Telescope’s data and the black hole image processing work could continue. This is another great example of how, when the world works together, we can accomplish some pretty remarkable achievements. Justin Bartel, the Science Museum of Virginia’s astronomer, has been on the edge of his seat much like science fans in the rest of the world. We had a chance to chat with him about a few things related to black holes and why studying them is of great value to both the scientific community and humanity as a whole! Here are some of Justin’s thoughts on this astronomy milestone.

Why is having a photo of a black hole so important?

Aside from the interesting scientific questions that will be addressed - and there are plenty - I think a lot of the excitement is related to the idiom "seeing is believing." We've tracked the orbits of stars around invisible massive companions, assuming all along that black holes were to blame.

We've detected x-rays emitted by super-heated gas that we assume is on the verge of passing into a black hole. But we've never actually seen the culprits in all these phenomena. They're elegant solutions to Einstein's equations but in a lot of ways they seem too extreme to be real, despite all the evidence we've gathered about them so far. But with a picture in hand, we'll have a new way to study them as physical objects rather than mathematical constructs. The structure revealed in the image should help confirm the accuracy of general relativity and perhaps help reveal how material gains the energy needed to fall into a black hole or spiral away in jets.

What's the most interesting part about this entire process?

What isn't interesting about taking the first-ever picture of a black hole? They took data from eight telescopes spread halfway across the planet and managed to combine it into one image. The delay caused by one set of observations getting stuck for a winter in Antarctica is a great part of the story too. They probably could've moved ahead without the SPT data, but they already have to do a lot of work to fill in the gaps in the data between the telescopes, so every hard drive full of data was a very important part of this project. And hopefully it's just the start - there are plans to add more telescopes to the EHT array in future years, so it's possible that sharper images will be collected in the future.

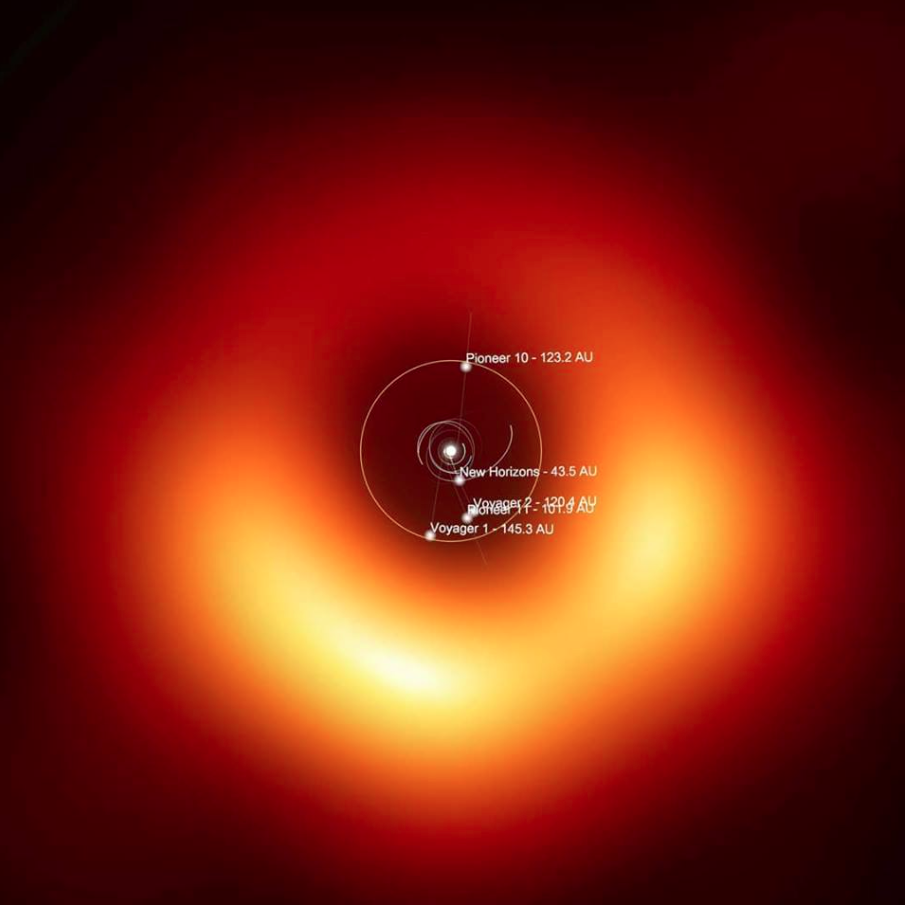

Can you put this discovery in context to our solar system? Spacecraft: Here the EHT image has been overlaid on the solar system with everything approximately to the correct scale. Close to the Sun you can just make out the orbits of Uranus, Neptune, and a few dwarf planets. The yellow circle marks the event horizon of the black hole, its true physical boundary. Nothing can escape this part of a black hole, but I've added the spacecraft escaping our solar system to the image and I find that Voyager 1 is the only one that's traveled a distance larger than the black hole's size.

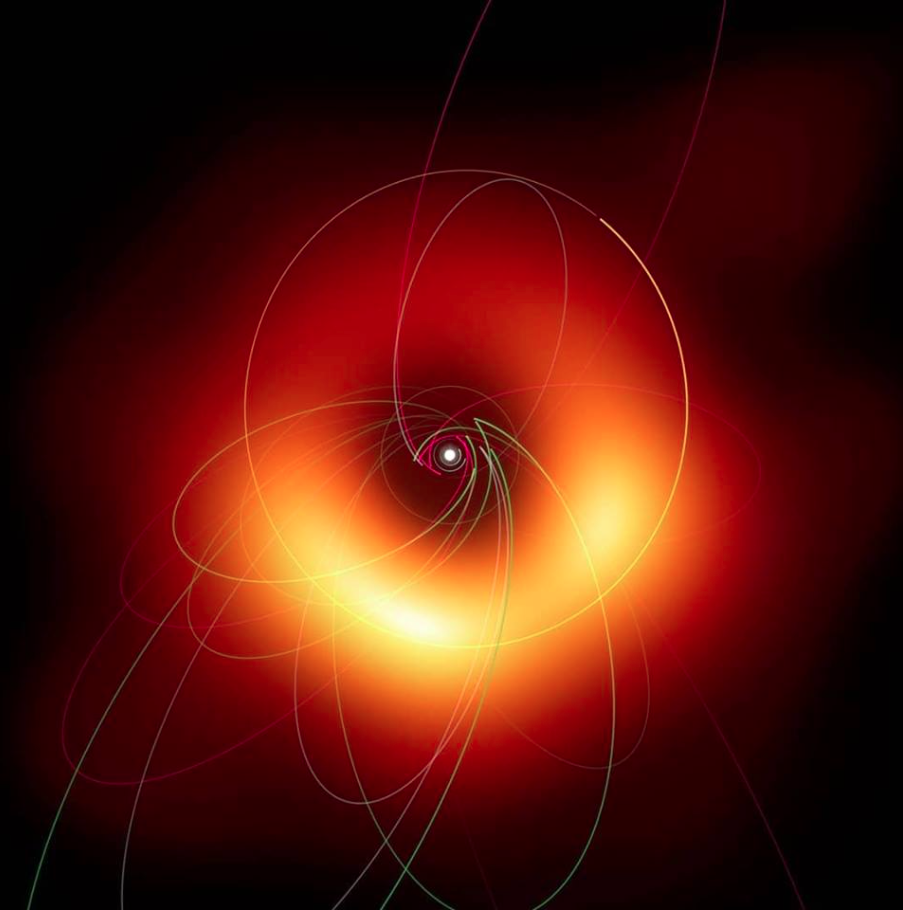

Planet Nine: Our most distant spacecraft are not the end of the solar system. Another ongoing puzzle in astronomy is whether another large planet is hiding in the outer solar system. Once again, the black hole image is displayed over the solar system. The long elliptical orbits extending past the edge of the image trace the paths of trans-Neptunian objects that have been used to predict the presence of Planet Nine; the planet's orbit is rounder, and intersects the bright ring around the shadow of the black hole. Because the "photon ring" in the EHT image is inside the smallest stable orbit around the black hole, we can say that Planet Nine is much better off in our solar system - if it were orbiting the M87 black hole instead, it would quickly spiral in, never to be seen again.

What is it that YOU want to know more about black holes:

The EHT produces images in radio waves, but I'm always curious about how things would really look to the human eye. It would also be interesting if we could achieve the resolution required to observe smaller black holes. The first black hole identified, Cygnus X-1, orbits a massive star, with material from the star spiraling in towards the black hole - actually seeing that process would be fascinating.

Black Hole vs Mike Ditka ... who wins?

If light can't beat a black hole, what chance does Ditka really have? Gotta go with the black hole.

Stay tuned to Question Your World for more breaking science news every single week. Visit Justin Bartel and his crew of astronomers at the Science Museum of Virginia in The Dome every single day!